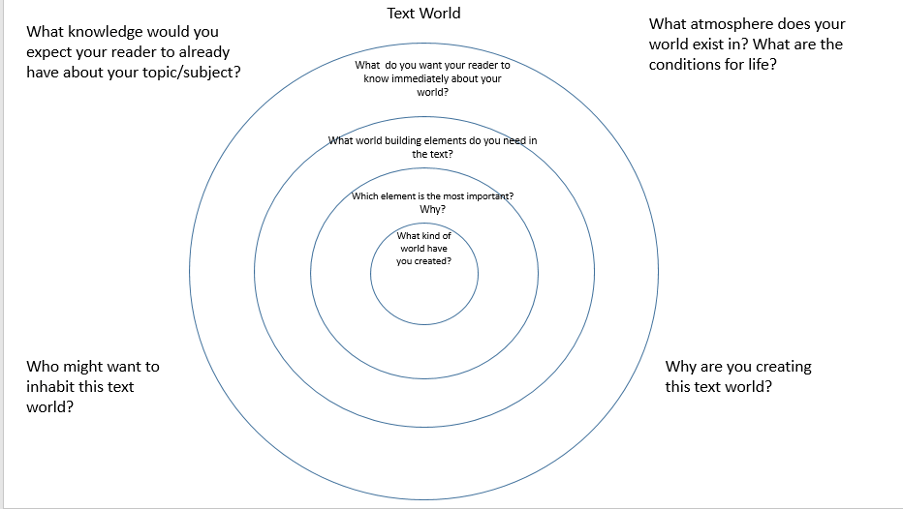

In Y10, the students had used TWT to help them plan their own narratives as in the resource below:

We’d also used this when considering the plot of The Tragedy of Macbeth. I’d asked the students to imagine how they would create a text world with an overly ambitious character in it. Through this method, they’d essentially written the plot themselves and constructed a schema that could be adapted as we began to learn about the storyline and historical context. It was a very exciting moment when the students realised that they had been thinking like one of the world’s greatest writers!

However, it was March 2022 before the project with Aston began and I didn’t want to introduce too many new things to Y11 so near to the exam. At the launch event for the project, we heard lectures on Text World Theory, Cognitive Linguistics, and Emotions and Reading and it was immediately obvious that ideas from these disciplines were going to help me solve some of the difficulties Y11 were experiencing, particularly in their recent mock exams. As I listened, I realised why a significant number of students had performed less well than normal on this particular paper. The class’s previous language analyses had mostly been clear (around six out of eight) with some in the perceptive band but this was different on the HE Bates (Hartop) extract, as some had fallen into level two rather than three. When speaking to colleagues, this had been the case across the year group and those who were examiners also said they noted poorer responses than in previous years on this paper.

In the TWT session, Marcello had asked us to sketch as he read an extract aloud to us. This activity revealed what the writer was foregrounding but also what was escaping the reader’s attention. The Hartop question asks about how the family is presented, but many answers focused solely on the father, and then mostly his physicality. When I got home, I drew the extract and could see how the father was ‘hiding’ the other family members – the students hadn’t misread as such – they had been directed skilfully by the writer. However, they were unaware of what this foregrounding said about the family dynamic. It was clear that the students needed to be explicitly taught how the writer was positioning them.

In the next lesson with Y11, I explained the concepts of foregrounding and had students sketch the extract. I then asked them to answer the question in relation to their sketch and consequently all the students discussed the family as a whole. They annotated their sketches with quotations and then used these to re-draft their first responses. The focus on the question was clearer: the inferences about the family had developed beyond the repetitive ‘they’re poor,’ ‘they’re hungry’; and they had started to explore more individual words rather than shallowly outlining metaphors. This resulted in all students moving back into level three (clear answers) and with many in level four (detailed answers).

After this, I looked at some difficulties the students had with non-fiction texts, particularly with being able to detect irony. We began by considering why non-fiction writers seemingly want to recreate existing worlds and the students commented that non-fiction is actually a type of fiction because it’s still a perception. We discussed the concepts of precepts and this helped students to see that language is used in very similar ways to the language of fiction as text worlds still need to be construed by the reader. Next, we discussed the term foregrounding and considered how all writers have to direct our focus and this act means that non-fiction is not a replica of the real world but, again, a perception of it: we discussed how a perception has been created in the writer’s head first and then how it’s shared with the reader for particular purposes.

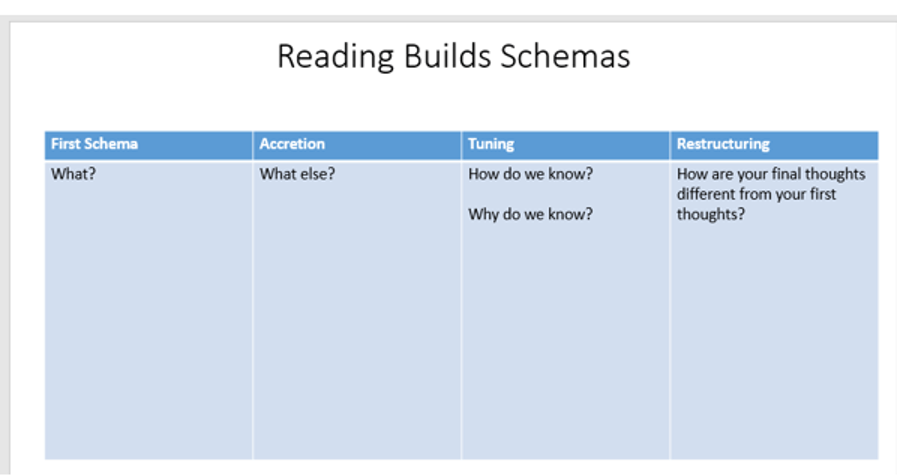

The students are used to using an adaptation of Labov’s model as a reading frame but this can be time consuming, especially in English Language Paper 2 where there are two texts to consider. The students, by this point, weren’t misreading the texts anymore but some understanding was still superficial. I considered the idea of schema accretion and thought this could be applied to non-fiction because it allowed for initial readings to adapt. This seemed to be useful as some students hadn’t picked up on the satirical and hyperbolic nature of a previous text (the Clive James extract about sweets).

I set out the process as below:

The students read an extract from Swift’s ‘A Modest Proposal’ independently first. They noted their initial ideas by considering what was being foregrounded: they commented on the mothers and children and how they were being defined in terms of numbers and quantity. We looked at the writer’s attitude, which appeared to be critical of the families. One student felt this wasn’t entirely serious, even at first glance. However, some students drew a link to Malthus to say that it was possible that the writer did think that the problem could be solved in this way. We then re-read and looked at how there might be evidence for an ironic reading. One student commented on the semantic field of food and how it moved from the more basic ‘stew’ to ‘fricassee’, which hinted at humour. They thought by bringing in more prestigious language there might be an attack on prestige itself. Another student looked at how the writer referred to his being assured by outside influences to suggest a distance between his real thoughts and those on the page. Another said that the title itself could be read differently and that modest might not suggest humility but a small and insignificant thought or idea.

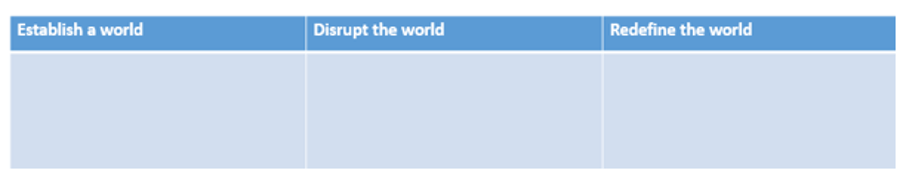

We then summarised our inferences by thinking of the sequence below:

We went from the foregrounding of the mothers and children as being the problem, to a focus on the ‘solution’ and what this new world would look like. The students commented that the writer wasn’t really supporting the proposal and therefore wasn’t attacking the victims of poverty but the thinking keeping it in place.

I asked the students how they found the reading frame of schema accretion. One said that it deliberately made her re-evaluate her first impressions and showed her that the writer wanted her to doubt her views. Another said it made the attitude of the writer clearer but allowed for other interpretations, as the first idea wasn’t a wrong idea exactly.

We decided to test the framework against a fictional text and looked at two extracts from A Christmas Carol. We read one with Belle and her husband. One student said that the first reading showed Scrooge almost accepting that Belle wasn’t right for him, but that the accretion reading let her focus on his actually not being able to stand to see her in her other life, however content she might be. We then discussed how Scrooge’s resentment in that moment ironically lead to his being more compassionate towards family life and we found this paradox really interesting. Another student said it suggested that knowing your own feelings is the first step toward empathy, even if your feelings aren’t the best ones. A third student said that Scrooge was thinking like both his present and past self in the extract. I felt this was a good time to introduce the concept of the enactor and to consider how an apparently simple question like the presentation of Scrooge meant we needed to look at all the versions of him.

We applied this to another extract – this was the one with Ignorance and Want. We considered how Scrooge’s words are repeated back to him and that the Ghost of Christmas Present becomes like the present enactor of Scrooge and how we see Scrooge reject his old enactor. This lead to a conversation about the importance of children in the novella and that the first enactor of Scrooge might be the most valid in Dickens’s view. We then considered Tiny Tim and the caroller and how they are exemplars of Christian values. We also looked at how Dickens seems to intrude to comment on how Christmas is a time for celebrating childhood. This was one of the most purposeful revision sessions as old knowledge was made more secure by linking it to a new framework, which can be applied across all the papers. The enthusiasm and engagement of the students with the schema theory was impressive also.

Not all students took part in this Easter session, so I adapted some of this for the first lesson back. To help students understand a letter written by a Victorian child, who is complaining of his school, I asked them to create their text world first. What would be in a text world where you are a child being treated unfairly in school? Then I asked them to modify this as their text world was now set in the Victorian age. We then compared their worlds with the letter and found many similarities e.g. modals, repetition, direct address etc. the students began to talk about how modal verbs were being used to suggest the possibility of harm rather than actual examples of harm and how this was to try and ‘sell’ an idea to the father of the boy. We then discussed how text world theory posits this and how texts present possible worlds to us also. This meant our discussion moved from how the writer was presenting an idea to how they were presenting a potential problem, leading to a broader range of techniques being discussed. This helped me to work out how TWT could be applied in the Y8 rhetoric scheme that I was planning at the time too.

After this, I went to support some Y11 students from another class. They showed me their response to the Hartop extract and explained their disappointment with their low marks. Both girls had written two pages, annotated the extract and broken down the question but had remained at level 2 and were quite despondent. Predictably, their answers focused on the dad and not the family and explored adjectives like ‘thin’ without linking them to a perception of the family itself. We diagrammed the extract and immediately they said the father was dominating. I asked how they knew and they spoke about where their attention was being directed. I told them to draw the dad as a shape and they drew a narrow rectangle. Next, I asked them to show how much space this thin shape was taking up and then they said his selfishness was overpowering the women in the family. I reassured them that the writer had wanted the dad to dominate their thoughts so they hadn’t read the text ‘wrong.’ One of the girls beamed at this and said it was like revealing a magic trick. They then redrafted their answers, explaining how their attention was being directed and what this said about the family. Their answers moved to Level Three.

Furthermore, in the 2022 cohort, there were five students I was particularly concerned about and I was able to give extra tuition to three of them, but the other two weren’t allocated this time on their timetables. I used TWT approaches in the extra sessions like the ones described above. At the end of the year the three students who’d received the extra sessions performed above target, achieving level eight in the GCSE exam. The other two students eventually achieved level six.

After this promising start, I’ve re-used the approaches with the current Y11 cohort. The head of KS4 has incorporated these strategies and I delivered training to the department on them. Four members of staff made immediate changes to their practice and an ECT colleague has had one to one support from me to help with developing the approaches in her classroom.

Below are some comments from staff following the training session:

After attending Emma’s training, I decided to use the principles of text world theory and cognitive linguistics in two ways: first to help students develop their inferential understanding by differentiating between speculative inferences based on their personal understanding of the text to analytical inferences based on the authorial intent within the sphere of each individual text world; and secondly to further master analysis through the exploration of polysemous words and their etymological origins vs the use of the word within the text sphere and time period. This has opened up possibilities for analysis far beyond previous methods of teaching and has become common practice in my classroom.’

Head of KS4

‘We looked at linguistic transformation/progress (the question was on Scrooges transformation) and looked at the language in ‘He became as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew’ and ‘a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner!’ through a cognitive linguistic frame. We said that the language in the second quotation was heavy and difficult compared to the lightness and simple lexis of the first quote, possibly mimicking the events and transformation of Scrooge. He has become a simpler and lighter character and the language reflects this.’

Teacher of KS4

I’ve also used these techniques in after-school sessions where I support students from across the whole Y11 cohort this year, but took it further by introducing the idea of possible text worlds in A Christmas Carol. I aimed to increase the raw marks of HPA students by exploring the novella as a metafictional text. One student commented as below:

‘You helped me properly boost myself into the perceptive band with more uncommon yet thoughtful ideas such as Dickens’ use of an intrusive author. This allowed me to create a high level, versatile conclusion revolving around how Dickens’ intrusive narration further develops his social comment, which I was able to implement into my actual GCSE answer. I’m confident that this paragraph will be a deciding factor during marking as it’s a more implicit perspective on A Christmas Carol.’

Here is an extract from her essay:

Overall, it’s made prevalent throughout the novella that Dickens is unequivocally on the side of philanthropy by implementing elements of intervention and projection of himself into the fictional world. This intrusion is established as early on as Stave 1, referencing ‘’Hamlet’s father”, an external text, and lingers on to Stave where the Ghost of Christmas present parallels Scrooge’s haughty statement of “Are there no prisons? Are there no workhouses”. It’s as through the Ghost has become synonymous with the overall narrator, Dickens, developing some sort of omniscience and knowledge of Scrooge prior to his moral conversion. As an intrusive author, we are constantly reminded of his presence so his influential and consistent message for social responsibility is also remembered regularly. Perhaps, these random occurrences of Dickens is almost emblematic of the Ghosts, trying to assimilate us into becoming spiritually rich rather than materially.

However, my favourite comment on the methods we’ve been using is the one below:

‘You do this thing where you do activities and i feel like it’s random but then at the everything comes together and I come out with the most amazing and smart high level work – it’s so cool!’

Y11 student.

These approaches are now a regular part of my teaching routine and I’ll be continuing to refine them across both key stages.